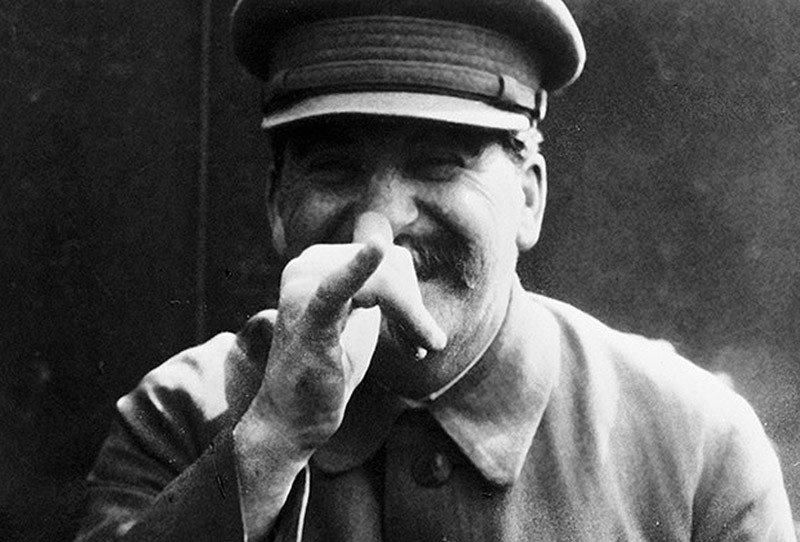

Is Russia Missing the Iron Fist? The Popularity of Joseph Stalin Hits Record High

2,318 views / 25 Aug 2015

Has Russia moved back to its old Soviet habit by isolating itself and returning to aggressive foreign policy? If yes, Joseph Stalin would become a perfect leader whom an increasing number of Russians started to support over the last decade. Has Putin’s government deliberately plunged the Russian society into nostalgia over Stalin, or has the support come from people themselves?

By Daria Zakharova

The period of Joseph Stalin was the most cruel and tragic event throughout the history of the Soviet Union, characterized by large-scale crimes against humanity. Such things and notions, like the Gulags (Soviet forced labor camps) and NKVD troika (commissions of three people who issued simplified, speedy sentences without a full trial), the terms “Enemy of the people” and Dekulakization (the campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportation and executions of better-off peasants and land owners) were all introduced and reinforced during the Stalin era. These anti-human and anti-democratic concepts maimed millions of innocent lives. Three years after the death of Stalin, the Soviet leadership began the process of acknowledgement of the consequences of his governance called “De-Stalinization.”

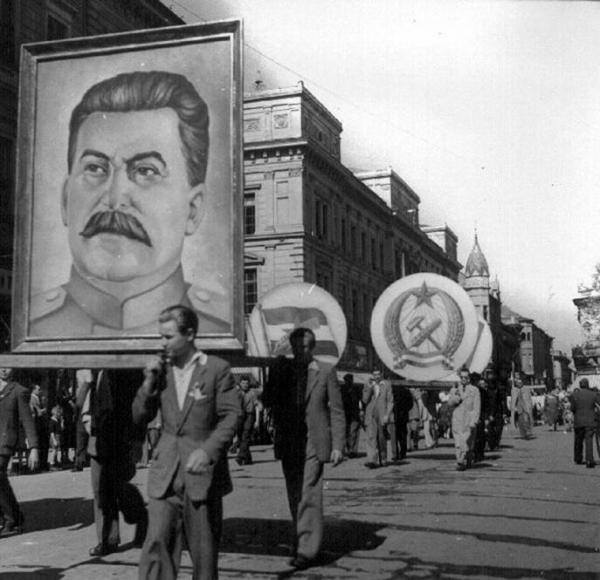

Initially, the concept of “De-Stalinization” was outlined by the report “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences” made by Stalin’s successor Nikita Khrushchev on 25 February 1956. The report laid responsibility for mass terror between the 1930s – 1950s on Joseph Stalin and his circle, marking the era of the so-called “Khrushchev Thaw.” The report was followed by numerous amnesties of the wide range of political prisoners from the Gulags, posthumous rehabilitation, as well as the mass demolition of Stalin’s monuments across the country. The process of Khrushchev’s “De-Stalinization” reached its apogee in the early 1960s when the Gulags were completely closed down and Stalin’s body was removed from the Lenin’s Mausoleum on the Red Square. “De-Stalinization” was resumed with a new vigor during the times of Perestroika in the late 1980s. Then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev granted posthumous rehabilitation to everyone sentenced and executed by NKVD, MGB (the Ministry for State Security) and other institutions that dealt with political repressions during Stalin. The era of glasnost (transparency) and the subsequent policy of strengthening freedom of speech, carried out by Boris Yeltsin gave the green light to the publication of numerous memories of the victims of repressions, literature and monographs, exposing the cult of personality and the scope of Stalin’s repressions.

While the presidency of Vladimir Putin has not been marked with direct administrative or judicial deviation from “De-Stalinization” outlined in Perestroika, some of the actions during his term seem to be undermining the previous efforts. With hardly a dozen memorial monuments to the victims of Stalin’s repressions (mostly built during the presidencies of Gorbachev and Yeltsin) across the 140-million country, more than 80 statues of Stalin currently exist in Russia. The majority of them was built during the Stalinist era and somehow avoided the mass demolition during the times of the Khrushchev Thaw, more than 35 busts and monuments have been erected over the last 15 years. The trend is especially disturbing because the erection of Stalin monuments hasn’t been deployed since 1956 and was resumed only during the first presidential term of Vladimir Putin in the early 2000s. This trend has introduced the neologism of “Stalinization” into the Russian language as opposed to the previous efforts of “De-Stalinization.”

The landmark of “Stalinization” was highlighted during the 60th anniversary of the 1945 Victory in the Great Patriotic War in 2005 when numerous departments of the Russian Communist Party appealed to local municipalities with the initiative to erect Stalin’s busts in their regions. According to the Communist Party [ed. here the author is of opinion that all four major political parties in Russia, including the Communist Party, are controlled by Putin, and therefore they aren’t independent], the initiative was due to the key role of Stalin’s personality in the victory and the need for commemoration of his memory. The Communist initiative was partially approved by municipal authorities and resulted in the erection of several Stalin busts and modest monuments around the country in 2005 and a dozen more during the following years.

Back in 2005, a 10-ton monument to Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt, the three leaders of the anti-Hitler coalition, was created as the gift of Russian architect Zurab Tseretelli to the Ukrainian city of Yalta located in the Crimean peninsula, but remained unplaced due to a strong resentment towards Stalin’s personality within the Ukrainian society. The monument was finally placed 10 years later – in February 2015, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea [ed. the terms “annexation” and “reunification” are both used to describe the situation around Crimea; the word choice depends on one’s belief]. In early 2015, the head of legal department of the Russian Communist Party Vladimir Solovyov announced the erection of at least 15 more Stalin busts across the country, devoted to the 70th anniversary of the Victory in the Great Patriotic War.

According to a recent survey carried out by the Levada Centre, Russia’s biggest non-governmental sociological research institution, approximately 52 percent of respondents gave a positive assessment to Stalin’s personality, while 45 percent of respondents said the repressions during the Stalin era were the measures defined by historical circumstances and are excused by the achievements of his government. Only 2 percent of respondents were worried and feared about the prospects of looming “Stalinization” in the contemporary Russian society.

In his interview to TV Channel Dozhd, Levada Centre director Lev Gudkov spoke about a gradual boost in Stalin’s approval among the Russian population during the last 10-15 years. He said there was a slight growth starting in 2004-2005 that peaked in 2012 when for the first time since the fall of the Soviet Union more than half of respondents expressed positive views of Stalin’s personality. Moreover, another Levada Centre survey in cooperation with the Carnegie Centre carried out in early 2015 found that 42 percent of respondents said Stalin was the greatest figure in Russian history. According to the Levada Centre, these numbers are significantly higher than those recorded in the 1990s during the presidencies of Gorbachev and Yeltsin. In contrast, between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, Stalin’s ratings of approval didn’t exceed 19-22 percent, Levada Centre deputy director Alexei Grazhdankin said.

Large-scale opposition protests in dozens of Russian cities in 2011 and 2012 after alleged ballot-rigging during the parliamentary and presidential elections caused a new wave of restrictive measures from the government. In addition to laws deterring civil rights, the issue of spreading non-patriotic beliefs among the youth, influenced by the rebel environment, was taken into account. After that stalemate, several brand new government-funded youth organizations were founded. The most famous Sut Vremeni (“The Essence of the Time”) and NOD (National Liberation Movement) founded in 2011 and 2012 respectively were mainly to form and unite the youth representing the anti-reformist ideas of pro-government and pro-Soviet traditional beliefs. The organizations held “anti-orange” meetings that had strong Stalinist inclinations.

The Sut Vremeni launched a massive campaign against “De-Stalinization” of the society. The initiative was a counter measure against the program “Commemoration Work of the Victims of Totalitarian Regime and Issues of the National Atonement” by the Russian Council on Civil Society and Human Rights. The latter project ended up on the table of then-Russian President Dmitry Medvedev who stressed that the country needed to acknowledge its tragic past in order to move on to the bright future. However, the Communist Party resolutely condemned the Russian Council on Civil Society and Human Right’s program, while the Sut Vremeni and NOD declared a de-facto war against it. The Sut Vremeni set a massive information campaign, stigmatizing the project as Russophobe and besmirching Russian and Soviet history. With several protests held by the Sut Vremeni, NOD and other pro-governmental organizations the project was dallied off.

The Putin’s government has abstained from any official assessments of the “side effects” of the Stalinist regime, but denied any waves of “Stalinization.” Many Russian liberals suggest that the gradual and thorough whitewash of atrocities done by Stalin’s repressions may be a pretext for excuse of the ongoing violations of human rights in Russia, as well as the increase of the government’s control over the society and the entrenchment of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) as the main instrument of governance. Many suggest the process may also be amongst the measures to strengthen and implicitly justify the long-drawn presidency of Vladimir Putin, as well as an excuse for monopolization of the authority and annihilation of political pluralism.

While the majority of the world sees the personality of Stalin, as well as the concepts “Stalinism” and “Stalinization,” simply as historical notions and the relic of the past, the modern Russia is at the crossroads. A new form of “Stalinization” might turn out to be the matter of future development for modern Russia.

The views and opinions contained in this article are those of the author. They do not necessarily represent the views of Russian Accent.

Stay tuned and be social, follow us on Twitter @RussAccent, like our page on Facebook/raccent and Vk.com/r_accent. Let’s be friends!

comments (2)

POST A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

You say that if Russian foreign policy is aggressive, then it is comparable with Stalin’s era. Why? Was Stalin’s foreign policy aggressive? More aggressive than Khrushchev’s? Brejnev’s? More aggressive than Trumen’s or other American presidents?

I could not get your message: Putin imposes the popularity of Stalin on society? Or society itself inclines, as you put it in the title, to “the iron fist”?

Dear Georgi, thanks for reading my article. I refer to a certain phenomena of ramping glorifying of Joseph Stalin in Russia during Vladimir Putin presidential terms. I tried to vouch this suggestion with as many empirical material as possible – amount of the monuments built, growing percentage of support among population etc.

If Russia starts building dozens of monuments to Nikita Khrushev or Harry Truman I can consider it as a disturbing issue as well. But yet there are no monuments to these people in the country, as well as majority of Russians do not refer to them as to the greatest people in history.

I tried to bring sufficient facts and points for readers to decide themselves whether the trend come from the vertical of authority, or from the nation itself. Stepping down my journalistic neutrality and unwillingness to obtrude my subjective point of view to the readers, I’d say there are both trends occurring. The government in frames of isolation, and anti-Western rhetoric searches for historical figures or lets say ‘red herrings’ to distract people and plunge them into euphory of, for instance, acquisition of Crimea (lets not to forget that the last leader who expanded the boundary of the country was Joseph Stalin as well). While people, especially, those behind the middle class, are happy to distract from impoverishment current governmental politics brings them and plunge into worshipping of such values as state integrity and expansion.